Your Lodger Ancestors

In the recent episodes of A House Through Time (BBC2 Thursdays 9pm) several of the fascinating characters whose lives have been researched by historian David Olusoga have been lodgers at 62 Falkner Street, Liverpool.

Whilst researching your ancestors on the nineteenth-century

censuses, you too may occasionally have been surprised to find that some of them

shared their homes with people who were not kin. Conversely, you may have

discovered that one or more of your ancestors spent time out of the family home

living as lodgers with another family in a different part of the British Isles.

In fact, hundreds of thousands of people lodged in the

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From the 1831 census onwards, the

terms ‘boarder’ and ‘lodger’ were used to define guests who (unlike ‘visitors’)

paid rent to the householder. Whereas ‘boarders’ shared the kitchen and dinner

table with the householder, ‘lodgers’ were expected to live and eat separately.

and/or on my dedicated facebook page Search My Ancestry (Facebook)

One of the main reasons for lodging in the late

nineteenth-century was the fact that, in the absence of other forms of

transport such as trams, buses and bicycles, people had to walk to work.

Workers may have lodged on a weekly basis returning home at the weekends, or

may have lodged seasonally, moving on when their contracts finished. From Manchester

Old and New by William Arthur Shaw, with illustrations after original

drawings by H. E. Tidmarsh, Vol II, Cassell and Co. 1896, p 3

|

Who Lodged?

For more sidelong glances at family history follow me: Ruth A Symes on Twitter

and/or on my dedicated facebook page Search My Ancestry (Facebook)

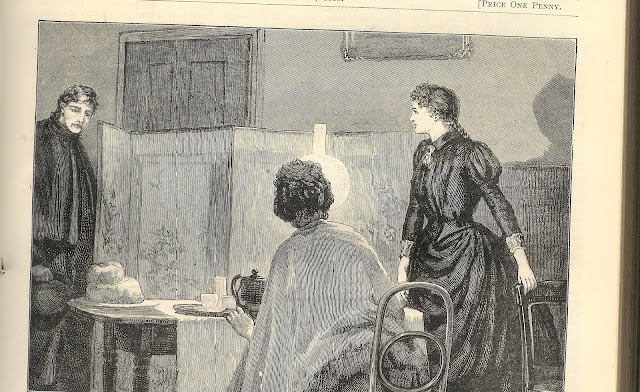

Lodgers threatened the cherished privacy of the Victorian

home. Girl’s Own Paper Vol IX, No 428 March 10th 1988

|

Lodging was a normal part of the life cycle for many young

working-class people, and of people of all classes who increasingly had more

reasons – work, education, leisure - to

be away from home. Typical lodgers included:

- Young

men who may have moved to the industrial centres from rural areas, or

indeed from other urban areas, to take up seasonal work. They included

railway workers, navvies and builders who were taking part in the great

processes of Victorian city construction

- Aspiring

lower-middle and professional class men including shop assistants, clerks,

accountants, and trainee clerics

- Young

women from trades such as dressmaking

- Immigrants

seeking to establish themselves in a new country. In the 1840s, after the

famine, many lodgers were of Irish origin. In the 1860s and later, in the

1880s, thousands of Jews from Eastern Europe came to Britain, first to

escape economic privation and later to escape persecution. They came, in

the main, to the Northern cities of Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool, and

often lodged with those who had come before

Who Took in Lodgers?

Censuses rarely record ordinary householders who took in

lodgers as ‘landlords’ or ‘landladies.’ It is worth remembering that many women

who are recorded simply as non-working ‘wives’ on the census may have actually

have been kept very busy tending to the needs of multiple paying guests. Other

women who took in lodgers were widows with no other adequate means of support.

They often took on the role of landlady in conjunction with some other work

such as dressmaking. Other frequent landlords were couples in late middle age

whose children had moved on, and young couples with young children (tots could

be bundled into the same bedroom as their parents, thus freeing up rooms). Clerics, doctors and schoolteachers often

took in lodgers to whom they might pass on their professional skills in a kind

of apprenticeship arrangement.

Where Did People Lodge?

Lodgers were to be found all over the British Isles in both

urban and rural communities and ‘lodgings’ could be anything from the dreaded

workhouse, to pubs, schools, dressmaking establishments, and (as the appetite

for holidays increased) to boarding houses in seaside resorts. From the middle

of the nineteenth century onwards, establishments of a certain size housing

several lodgers were designated as ‘Common Lodging Houses’ and had to follow

rules and regulations laid down in the Common Lodging Houses Acts of 1851 and

1853 and other related legislation.

In cities like Manchester

- where there was a severe shortage of municipal housing – it was more

usual to hold a house as a tenant rather than as an owner. The setting of rents

was largely unregulated and, faced with high rents, tenants were often forced

into subletting to lodgers to avoid eviction. Lodgings were invariably situated

in fairly poor areas, but not, however, in the very poorest areas since

here severe overcrowding meant that subletting to strangers was nearly

impossible.

Early trade organisations often provided their members with

lists of potential lodging houses in areas to which they intended to move.

Families might advertise lodgings on cards placed in their windows. From the

1870s onwards, Common Lodging Houses were required by Act of Parliament to

display a notice stating their status in some conspicuous place. Also from this

period, names of lodging housekeepers had to be registered by urban and

district councils.

What Could Lodgers Expect for their Rent?

Lodgers may have been provided with an unfurnished room to

which they would have been expected to bring their own effects. Alternatively,

they may have rented a room ‘all found’

- that is, furnished by the landlords. Usually lodging was undertaken on

the condition that ‘attendance, light and firing’ were supplied. ‘Attendance’

covered a range of services from cleaning the lodger’s room to carrying water,

emptying slops such as waste waters and chamber-pots, making fires, running

errands and cleaning boots. ‘Light’ referred to the fact that candles would be

supplied and ‘firing’ to the provision of coal. Lodgers might cook their own

meals on their own fires, or might buy their own food and pay a small sum for

it to be cooked by the landlady.

Male and female lodgers would have received different sorts

of treatment. A landlady might have done a male lodger’s washing, for example,

whilst a female lodger would have been expected to do her own. It is unlikely

that we will ever be able to find out exactly what working-class landlords

might have charged, but the chances are that they were not making much of a

profit. Taking in lodgers was part of a subsistence economy in many cases.

Lodgers, the Law and Morality

Under apprenticeship arrangements, eighteenth-century

lodgers had tended to learn a skill during the time they lived in the houses of

others. But the nineteenth century was a very different world. Now, lodgers

were expected to pay for their accommodation in cash and, generally, did not

receive any training in return. They also had far more freedom; landlords were

no longer their masters. As a result of these changes, lodging came to take on

a new, and much more downmarket character in the Victorian city.

The middle classes began to view lodgers and those who ran

lodgings with disdain and suspicion. Lodging houses were popularly assumed to

be dirty, and their communal facilities to foster immorality. In the imaginations of the middle-classes at

least, young male lodgers posed a threat to the virtue of the women in the

household. And female lodgers too came in for censure – it was assumed that

they were ‘looser’ than domestic servants. Another aspect of lodging disliked

by the middle classes was the fact that it mixed together the private world of

domestic life with the public world of business. For those middle-class

Victorians who believed in the separation of the two worlds, this was something

to be avoided on all counts.

For more sidelong glances at family history follow me: Ruth A Symes on Twitter

and/or on my dedicated facebook page Search My Ancestry (Facebook)

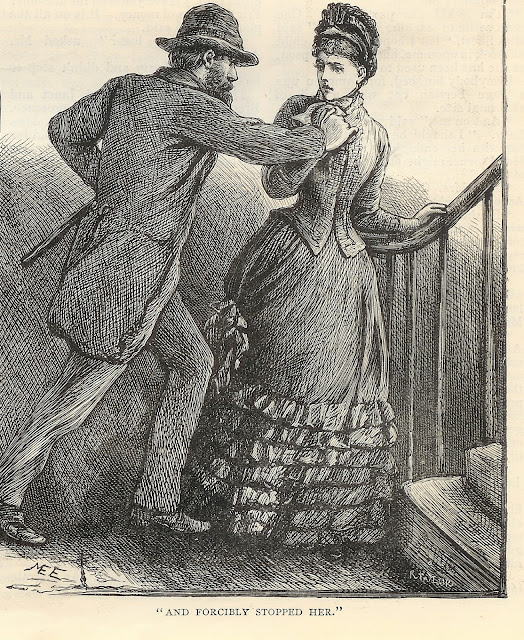

In the popular imagination, male lodgers might,

at any moment, try to defile female members of the household on the backstairs!

Girl’s Own Paper Vol IX, No 410, November 5th 1887.

|

This negative feeling towards lodgers and lodging houses

resulted in a number of laws being passed in the 1850s to try to ameliorate the

conditions in some of the larger so-called Common Lodging Houses. In 1851 and

1853, the Common Lodging Houses Acts allowed specially appointed agents of the

Metropolitan Police (and later the police in the provinces) the right to enter

and search lodging houses at any time of the day or night to check on the

numbers of people sleeping there, the mixing of the sexes in the sleeping

arrangements, and the sanitary arrangements. Later Acts went still further in

tackling the perceived filth and immorality of some of the larger lodging

houses. Small-scale lodging arrangements in private families were not affected

by these Acts.

After World World War I, many middle-class widows whose

husbands had been killed were compelled to take in lodgers or ‘P.G.s’ (paying

guests) to make ends meet. From this point onwards the image of lodging did

improve slightly. It was, after all, an activity that actually enriched

communities. The money brought in by lodgers helped many working-class families

survive and the very existence of lodgings enabled many more to move to where

work was and, in turn, support their own families by sending money back home.

And perhaps just as significantly, having a lodger – or lodgers – brought

families into contact with people from other places, classes and cultures and

gave them a window on the world that they would not otherwise have had.

If you have been inspired by David Olusoga's 'A House Through Time' and have an interesting story about a lodger in your family, please use the COMMENTS box below to tell us about it.

If you have enjoyed this article, please share on social media using the icons at the bottom of this post.

Why not read another article related to 'A House Through Time'?

For more sidelong glances at family history follow me: Ruth A Symes on Twitter

and/or on my dedicated facebook page Search My Ancestry (Facebook)

Want to find out more about your house and your street. Take a look at this project on 20 streets in Brighton and Hove for lots of ideas on how to go about it. My House My Street Project.

Useful Books

Barker, Hannah, The Business of Women: Female Enterprise

and Urban Development in Northern England, 1760-1830, OUP, 2006.

Leonore Davidoff, ‘The Separation of Home and Work?

Landladies and Lodgers in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century England’, in

Burman, Sandra, Fit Work for Women, Croom Helm, 1979.

Drake, Michael, Time, Family and Community: Perspectives

on Family and Community History, WileyBlackwell, 1993.

Symes, Ruth A. Unearthing Family Tree Mysteries Pen and Sword Books, 2016.

Symes, Ruth A. Family First: Tracing Relationships in the Past, Pen and Sword Books, 2016.

Symes, Ruth A. Unearthing Family Tree Mysteries Pen and Sword Books, 2016.

Symes, Ruth A. Family First: Tracing Relationships in the Past, Pen and Sword Books, 2016.

Walton, John, The Blackpool Landlady, Manchester

University Press, 1978.

Useful Websites

http://www.workhouses.org.uk/index.html?dosshouses/dosshouses.shtml

Information and images of Common Lodging Houses mainly in London.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/hitch/gendocs/lodging.html

Extract from Dickens’s Dictionary of London, 1888 on lodging houses and

their location.

This article was first published in Discover My Past England online magazine.

#ahousethroughtime #davidolusoga #familytree #ancestors #ancestry #neighbours #neighbors #certificates #neighbourhoods #neighborhoods #genealogy #familyhistory #househistory #newspapers #courtrecords #archives #Liverpool #lodgers #Europeanancestors, #census, #England, #familyhistory, #familyresearch, #researchservices #familyhistoryresearch #familytreeresearch #genealogist

This article was first published in Discover My Past England online magazine.

Four family history books with a difference....

For women's history and social history books - competitive prices and a great service - visit:

No comments:

Post a Comment