Twitter: https://twitter.com/RuthaSymes

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Searchmyancestry/

A Watery Grave

When I first found out that three of my ancestors drowned –

in separate incidents - in the same piece of water, the Leeds-Liverpool Canal

in Wigan, Lancashire, I was rather shocked at the macabre coincidence and

determined to find out more.

|

|

Commerical Inn and the Leeds Liverpool canal at Aspull, Wigan. Enoch Fletcher was drinking here on the night of his death and it is here that his

body was brought for the inquest.

|

Unfortunately, it turns out that death by drowning was an

all too common feature of life in industrial towns in the nineteenth century.

Canals and rivers could be death traps in more ways than one. Towpaths, which

ran beside pubs and hostelries, were often unpaved and slippery late at night;

they provided a conveniently ill-lit venue for drunken fights, robberies and

muggings. Local waterways also proved a popular repository for unwanted babies (some

aborted, and some the victims of infanticide), and last but not least, there

was a significant rise in the number of suicides by drowning in Britain in the

last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Charles Dickens’s novel, Our Mutual Friend (1865) famously

opens with the unsavoury character, Gaffer Hexam, and his daughter ‘Lizzie,’ sculling along the dark

river Thames in a small boat looking for the bodies of the dead. Hexam

describes the results of his recent trawls dispassionately as a mixed bunch: a

sailor with tattoos on his arm, a young woman in grey boots and wearing linen

marked with a cross, a man with a nasty cut over his eye, two sisters who tied

themselves together with a handkerchief, and a drunken old chap in a pair of

slippers and a nightcap who had drowned because he had entered into a bet to

‘make a hole in the water for a quart of rum.’

I don’t know what my great-great-grandfather Enoch Fletcher

was wearing when the Leeds-Liverpool canal claimed his life in February 1869.

What I do know is that after a night out, the unfortunate fellow, was making

his usual early morning trip home from the Commercial Inn at Top Lock, in the district of Aspull, when he,

apparently, stumbled and fell into the water. His death certificate records

‘Drowning in the Leeds-Liverpool Canal. Fell in accidentally while

intoxicated.’

Drowned bodies, in the first instance, I have discovered,

drop to the bottom of canals. If the weather is cold, as I am sure it was in

Wigan that February, they can remain below for sometime. From the date of

Enoch’s death certificate, however (just a week later), it is obvious that his

body was raised to the surface pretty quickly, probably with a ‘keb’ - or iron rake - normally used to retrieve

coal and other articles from the canal bed. His swollen corpse would then have

been brought back to the Commercial Inn for identification and for the inquest.

Records of such inquests often turn up a few days after the date of death in

local papers and I was satisfied to find a record of the inquest for Enoch on

the relevant microfiche of The Wigan

Observer and District Advertiser.

|

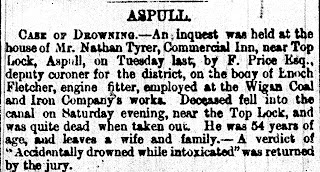

| Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, Saturday February 20th 1869 |

CASE OF DROWNING

An inquest was held at the house of Mr Nathan Tyrer, Commercial Inn, near Top

Lock, Aspull on Tuesday last, by F. Price Esq., deputy coroner for the

district, on the body of Enoch Fletcher, engine fitter, employed at the Wigan

Coal and Iron Company’s Works. Deceased fell into the canal on Saturday

evening, near the Top Lock, and was quite dead when taken out. He was 54 years

of age, and leaves a wife and family. A verdict of ‘accidentally drowned while

intoxicated’ was returned by the jury.

The drowning of Enoch led me to ask questions about the easy

availability of alcohol in Wigan in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

By 1889, the Commercial Inn was one of 139 public houses, 62 beer houses and

eight breweries in the town. A lot of men (and women too) probably stumbled

home dangerously drunk at around that time. Even today, approximately two

thirds of all adult males found drowning have consumed alcohol, and safety

advice in swimming pools and around lakes warns that alcohol impairs the

judgement, balance and co-ordination that are essential for swimming well and

for avoiding hazards in water.

By strange co-incidence, just over a decade after Enoch’s death, in 1881, another of my great –great – grandfathers, Lawrence Cooke, a 77 year old cotton spinner and journeyman, met his end in similar circumstances in the same canal. Lawrence drowned in the Westwood Park area of Wigan and the death certificate says simply, ‘Found Drowned.’ I don’t know the real reason why Lawrence died. Like all victims of drowning, he would have been lying face down in the water with his head hanging and it is likely that his corpse would have been bruised and discoloured. Nowadays, it is possible to tell from forensic tests whether a drowned person stopped breathing before or after they entered the water, but in the nineteenth century, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain whether Lawrence’s injuries were the result of buffeting by the water, or by injuries sustained before death.

A recent study by the Economic and Social Research Council on Violence in the North West suggests that official homicide figures in the nineteenth century grossly underestimated the actual amount of murder, manslaughter and infanticide in the second half of the nineteenth century. The study suggests that open verdicts were often returned ‘in the case of adults who had died under suspicious circumstances, especially those fished out of canals or the River Mersey.’ The phrase ‘Found drowned’ on a nineteenth-century death certificate is really just a convenient catch-all for a multitude of possible circumstances of death - it simply means that the body was found in water.

Providing the bodies of the drowned reached the hands of the

Victorian police quickly, the pockets of

any clothing would be searched, and details of the contents would be recorded

in the local newspaper account of the death. In the case of unidentified

persons, significant aspects of appearance and a list of possessions would be described on posters that would be put up

around the town in the hope that these would provide clues to identification.

While searching the Wigan newspaper records, I came across

the details of a case of drowning that occurred in 1860. On this occasion,

William Smith, a farm servant (and thankfully no relation of mine), had fallen

into the Leeds-Liverpool canal from a cart passing over Martland Mill Bridge.

When his pockets were emptied, they revealed ‘one penny in copper and a pipe.’

As a family historian, there is

nothing that gives you quite as much of a thrill as finding out what was in the

pockets of your own ancestor on the night he or she died. I was, therefore,

intrigued to discover that when great-great grandfather number two was

pulled out of the canal, his pockets yielded two items: ‘a knife and an apple,’ poignant reminders of

a simple life suddenly curtailed. Of course, the fact that there was no money

in Lawrence’s pockets allowed me to

speculate that he might have been robbed and then murdered in the park on his

last journey home. Perhaps, I mused, he was unable to get to his knife in

time….

The third member of my family to lose her life in the same

great commercial waterway was my great-great aunt, Margaret Daniels, ‘a factory

hand.’ Margaret drowned on 8th March 1874, ‘above No. 8 Lock, Upper Ince’ at the tender

age of just twelve. The Deputy Registrar for Wigan, William Henry Milligan, was

obviously so fascinated by the detail of the Coroner’s Report of the drowning

that he filled in the space accorded to ‘Cause of Death’ on Margaret’s death

certificate, with far more detail than was customary. The record reads:

‘Drowned in canal. Passing along bank in evening carrying umbrella. Accident –

in the water 2 days.’ I am still speculating about why a twelve-year-old girl

ended up meeting her end in murky waters just a few hundred yards from her

home, and particularly why she had such a tight grip on her umbrella that she

was still clutching it when her body was recovered.

An apple, a knife and an umbrella - I count myself fortunate

that I have had these clues to my ancestors last moments. Sometimes, of course,

the victims of drowning were fleeced before they reached police hands by those

passers by, or professional boatmen, who actually brought the bodies ashore.

Dickens’s Gaffer Hexam unscrupulously ransacked of the pockets of those he

pulled from the river. When questioned, he would insist, with mock innocence

that it was probably the ‘wash of the tide’ that emptied pockets and turned

them inside out!

Charles Dickens was not the only Victorian to be fascinated by the idea of drowning. Literature and art are littered with many examples, from the poignant double death of brother and sister Tom and Maggie Tulliver at the end of George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss (1860) to the iconic portrait of Shakespeare’s Ophelia by John Everett Millais (1851-2). For my ancestors, and their families, of course, the experience of asphyxiation by water would have been anything but poetic. But the records of their deaths did provide a prompt for my imagination, allowing me to catch glimpses here and there – like reflections on water - of the perilous industrial world they inhabited.

Click here for more on books by Ruth A. Symes

Useful websites and books

http://www.wiganworld.co.uk Website on history of Wigan

http://www1.rhbnc.ac.uk/sociopolitical-science/vrp/Findings/rfarcher.PDF

Web address for the paper ‘Violence in the

North-West with Special Reference to Liverpool and Manchester, 1850-1914’

Economic and Social Research Council.

www.penninewaterways.co.uk Website for Pennine Waterways (includes lots of photographs)

www.mike.clarke.zen.co.uk/Englishcanals.htm - A brief history of English canals

Nicoletti, L.J., ‘Downward Mobility: Victorian Women, Suicide and London’s Bridge of Sighs,’ Literary London 2.1 March 2004

Keywords: European ancestors, ancestry, family history, genealogy, death, death certificates, England, English, drowning

No comments:

Post a Comment